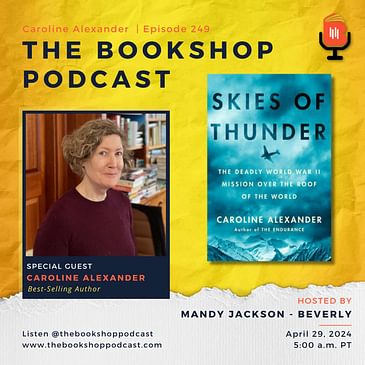

Embark on a historical odyssey as Caroline Alexander, New York Times Bestselling Author and acclaimed contributor to The New Yorker and National Geographic, unveils the lesser-known sagas of World War II's China-Burma-India theatre in her new book, Skies of Thunder: The Deadly World War II Mission Over The Roof Of The World.

With a background steeped in philosophy, theology, and classics, Caroline offers a rich tapestry of stories that captures the heroism and daunting challenges faced by those who shaped pivotal moments in history. Her transition from a voracious reader to a celebrated author is a testament to the power of classical languages in enhancing narrative precision, a theme that resonates deeply throughout our conversation.

The episode traverses the rugged landscapes of the 1940s, retracing the steps of untrained civilians who sculpted the vital Burma Road with nothing but rudimentary tools. Caroline's meticulous research paints a vivid picture of their struggle and the strategic importance of the road, inviting us to view their accomplishments as more than a military feat but an enduring emblem of the human spirit. The gripping accounts of the pilots who risked their lives over the treacherous "Hump" region come to life, showcasing their bravery in the face of primitive navigation equipment, daunting weather, enemy fire, and the Himalayas.

Amid the roar of engines and the call of duty, we hear the personal story of fighter pilot Robert T. Boody and gain an intimate look at the air transport command's overlooked dangers. Caroline's narrative explores the intricate web of allied relations, highlighting the strategic and geopolitical intricacies that shaped World War II's theatre in Asia. This episode celebrates the launch of Skies of Thunder and honors the legacy of those who navigated the deadliest skies with unwavering resolve. Join us to uncover the trials and triumphs that defined an era where courage soared above the clouds.

Skies of Thunder: The Deadly World War II Mission Over the Roof of the World, Caroline Alexander

The Bookshop Podcast

Mandy Jackson-Beverly

Social Media Links

Speaker 1: Hi, my name is Mandy Jackson-Beverly and I'm a

00:00:14

bibliophile.

00:00:15

Welcome to the Bookshop Podcast .

00:00:18

Each week, I present interviews with authors, independent

00:00:22

bookshop owners and booksellers from around the globe,

00:00:29

publishing professionals and specialists in subjects dear to

00:00:31

my heart the environment and social justice.

00:00:32

To help the show reach more people, please share episodes

00:00:35

with friends and family and on social media, and remember to

00:00:38

subscribe and leave a review wherever you listen to this

00:00:42

podcast.

00:00:42

To financially support the show , go to thebookshoppodcastcom,

00:00:47

click on Support the Show and you can donate through.

00:00:50

Buy Me a Coffee.

00:00:51

Okay, now let's get on with the show.

00:00:54

You're listening to Episode 249 .

00:01:00

Caroline Alexander was born in Florida to British parents and

00:01:04

has lived in Europe, africa and the Caribbean.

00:01:07

She studied philosophy and theology at Oxford as a Rhodes

00:01:11

Scholar and has a doctorate in classics from Columbia

00:01:14

University.

00:01:15

She is the author of the New York Times bestseller the

00:01:19

Endurance Shackleton's legendary Antarctic expedition, which has

00:01:23

been translated into 13 languages.

00:01:26

Her other books include Mrs Chippy's Last Expedition, the

00:01:31

Journal of the Endurance's Cat, the Bounty, the True Story of

00:01:35

the Mutiny on the Bounty, the War that Killed Achilles and her

00:01:39

latest Skies of Thunder.

00:01:41

Ms Alexander writes frequently for the New Yorker and National

00:01:43

Geographic.

00:01:43

Here's the synopsis for Skies of Thunder.

00:01:44

Miss Alexander writes frequently for the New Yorker

00:01:45

and National Geographic.

00:01:45

Here's the synopsis for Skies of Thunder.

00:01:49

In April 1942, the Imperial Japanese Army steamrolled

00:01:53

through Burma, capturing the only ground route from India to

00:01:57

China.

00:01:57

Supplies to this critical zone would now have to come from

00:02:01

India by air, meaning across the Himalayas on the most hazardous

00:02:06

air route in the world.

00:02:07

Skies of Thunder is the story of an epic human endeavor, one

00:02:12

in which allied troops faced the monumental challenges of

00:02:15

operating from airfields hacked from the jungle and taking on

00:02:19

the hump the fearsome mountain barrier that defined the air

00:02:22

route.

00:02:22

They flew fickle, untested aircraft through monsoons and

00:02:27

enemy fire, with inaccurate maps and only primitive navigation

00:02:31

technology.

00:02:31

The result was a litany of both deadly crashes and astonishing

00:02:36

feats of survival.

00:02:37

The most chaotic of all the war's arenas, the

00:02:40

China-Burma-India Theatre, was further confused by the

00:02:44

conflicting political interests of Roosevelt, churchill and

00:02:47

their demanding nominal ally, chiang Kai-shek.

00:02:49

Hi, caroline, and welcome to the show.

00:02:52

It's wonderful to have you here .

00:02:55

Speaker 2: Thank you very much.

00:02:56

I'm excited to be here.

00:02:58

Speaker 1: Congratulations on your new book, skies of Thunder

00:03:01

the Deadly World War II Mission Over the the roof of the world.

00:03:04

It is magnificent, thank you.

00:03:06

I knew nothing about this particular part of World War II

00:03:12

pertaining to Burma and I found it absolutely fascinating.

00:03:16

And we'll get more into your writing of the book a little

00:03:19

further on into our conversation .

00:03:21

But congratulations, it's absolutely wonderful.

00:03:24

The book is coming out on May 14th and I highly recommend

00:03:29

pre-ordering this book.

00:03:30

Okay, let's begin with learning about you and your diverse

00:03:34

creative endeavors from professor, author and filmmaker.

00:03:39

Speaker 2: Well, I think of myself first and foremost as a

00:03:42

writer, and that was what I had always, always wanted to be from

00:03:46

.

00:03:46

I can remember wanting to be a writer at age six.

00:03:49

At that age who knows what that really meant, but I loved books

00:03:54

and I was a voracious reader.

00:03:56

I was very fortunate to grow up without television, so my

00:04:02

sister and I read and read, and read, and somewhere along the

00:04:05

line I read a.

00:04:07

I went to a high school that had no structured I almost want

00:04:12

to say instruction of any kind, but that's not quite fair.

00:04:15

But let's say it was wide ranging, we were given a lot of

00:04:18

latitude and somewhere in the course of that I stumbled on a

00:04:22

translation of the Iliad by the great Richmond Latimore, when I

00:04:27

was about 14, and it was life-changing.

00:04:31

I responded to the story, the characters, the speeches, the

00:04:37

whole sense of this being maybe quasi-historic in a very

00:04:42

visceral way and decided that I needed to learn Greek to read

00:04:47

the Iliad.

00:04:47

Oh my goodness.

00:04:50

I grew up in the United States and classical instruction is not

00:04:55

normative unless one goes to sort of prep school type things.

00:04:59

So I had to wait until I went early to university.

00:05:03

So I had to wait until I went early to university, graduated

00:05:10

from high school early a great part to get on with my program.

00:05:11

But I was also becoming increasingly aware of how many

00:05:15

authors that I read and enjoyed had been classicists.

00:05:18

So I was very respectful of what a traditional Greek and

00:05:23

Latin curriculum can do for a young writer, or a writer a

00:05:29

yearning writer, let's say and I believe that the use of what

00:05:33

I'd almost call these shadow languages, these languages that

00:05:37

one is never going to really speak, is a very good training

00:05:42

for word precision.

00:05:44

It means you're translating for yourself in a private way, as

00:05:50

opposed to learning, say, french or Spanish or German, which is

00:05:53

going to be for public discourse .

00:05:55

So I'm a great advocate for that for a writer.

00:05:58

And then, when I came out of that, a friend and I put

00:06:03

together, when I was at university in England, an

00:06:05

expedition to collect insects in Borneo.

00:06:08

We had undertaken it to travel the world and to see the world

00:06:13

and we were very ill-qualified for it.

00:06:15

It was really a game of bluff, and we raised money based on the

00:06:18

name of Oxford as opposed to any skill, but anyway we went

00:06:20

off to do it of Oxford as opposed to any skill, but anyway

00:06:23

we went off to do it.

00:06:24

And then when I came back and I was at graduate school at

00:06:28

Columbia University for my doctoral studies in Classics, I

00:06:51

had the urge to write about this experience and sort of poured

00:06:52

it out over on these new phenomena called word processors

00:06:54

that we had in the graduate room and showed what I'd written

00:06:56

about the North Borneo expedition, as I had called it,

00:06:57

to a friend.

00:06:57

And long story short, the friend who was one of my

00:07:01

professors had a very close friend who was a literary agent

00:07:07

and he took the manuscript and about, I'd say, two, three weeks

00:07:13

later I got a call that the new editor at the New Yorker, bob

00:07:17

Gottlieb, had chosen this piece to be the first piece he would

00:07:22

publish as editor of that historic magazine.

00:07:26

And so suddenly I was a writer.

00:07:29

While I always remember there was a sign in a student bar in

00:07:36

Tallahassee, florida, where I grew up, that said 10 minutes

00:07:39

ago I couldn't spell bartender, and now I are one.

00:07:43

I couldn't spell bartender and now I are one, you know, and I

00:07:51

sort of thought about that as my writing career that suddenly I

00:07:55

were one and so I sort of balanced this creative so-called

00:07:59

creative writing, if you will with my doctoral duties.

00:08:03

And when I emerged at the end with my doctorate, to the

00:08:08

satisfaction of my mother, I felt now I could embark on a

00:08:13

freelance career, that I sort of knew the perils but I had a

00:08:17

little bit of traction.

00:08:18

So that was how I became a writer.

00:08:21

But I carry classics with me a lot of the way, and very

00:08:26

specifically the Endurance which was, if you will, my

00:08:31

breakthrough book about Shackleton's extraordinary epic

00:08:34

of survival, was very much written with the Iliad in mind.

00:08:38

There was a kind of terseness of language where you rely on

00:08:44

the flow of a narrative without having to ever get over.

00:08:47

Homer is never overblown.

00:08:49

There's actually, despite appearances, a very simplicity

00:08:55

of language, very fast flowing, very straightforward in its way,

00:09:00

but mostly the whole structure of that typically that story's

00:09:05

always told ends with the heroic ending of the rescue of the men

00:09:10

.

00:09:10

But that would be like ending the Iliad when Achilles kills

00:09:15

Hector.

00:09:15

That's not where the Iliad ends .

00:09:18

The Iliad ends on the mortal note, with Achilles alone in the

00:09:23

tent and Priam coming to him, and the two men reflecting and

00:09:27

acknowledging that they've had all this loss of life and they

00:09:31

too are going to die.

00:09:32

And I thought we need to know these were mortal men of

00:09:37

Shackleton's, not just legendary heroes.

00:09:40

And so I traced all the men, found out what happened to them

00:09:45

after the expedition, which was sort of innovative at that time

00:09:48

but I can say was directly inspired by the Iliad.

00:09:51

So I lurched forward and I seemed to gravitate to epic

00:09:57

stories, and Skies of Thunder is another epic story in my view.

00:10:02

And you write them so well.

00:10:04

Speaker 1: Well, thank you.

00:10:04

Where did the filmmaking come in?

00:10:07

Speaker 2: The filmmaking came in.

00:10:08

I had a very dear friend of mine who was a very gifted

00:10:11

documentary filmmaker, a pioneer named George Butler, whose

00:10:19

best-known work was Pumping Iron , where he discovered Arnold

00:10:23

Schwarzenegger oh my goodness.

00:10:25

But he wrote.

00:10:26

He had a very interesting background.

00:10:29

He was a British American, grew up in Somalia, lived in Jamaica

00:10:34

and just very curious and unorthodox and did beautiful

00:10:40

documentaries with the kind of production value that people

00:10:44

invest in feature films.

00:10:46

And so I wrote for him specifically on a number of

00:10:51

projects, including a documentary on the Endurance.

00:10:54

Very tragically, to say, he died young 78, at the end of 2021,

00:11:01

in the midst of making this wonderful IMAX movie about the

00:11:05

tigers of the Sundarbans, the mangrove swamp area in

00:11:10

Bangladesh and India, but a great, quirky conservation story

00:11:15

, and I had been the writer of that and had been a sort of

00:11:21

assisting as a producer.

00:11:22

He was afflicted with Parkinson's and when he passed

00:11:27

away, his producer and I finished the movie, which we've

00:11:32

in fact just recently done.

00:11:34

So I'm very cautious about claiming to be a filmmaker.

00:11:37

I feel I was the partner and participant of a very specific,

00:11:43

narrow range of projects.

00:11:45

That said, I'm hoping now, with the producer, to do an IMAX for

00:11:50

the Science Center venues one of these shorts, if you will, on

00:11:55

the oracles of ancient Greece, which I think is a lot of new

00:11:59

information and technologies.

00:12:01

That could be very exciting to do that.

00:12:03

So if that happens and it takes a miracle to make a movie if

00:12:08

that happens I would more forthrightly claim to be a

00:12:12

filmmaker.

00:12:13

Speaker 1: Well, that project sounds intriguing and the

00:12:16

documentary you made earlier with your friend is that Tiger,

00:12:19

tiger, yes, yes, it's out, isn't it?

00:12:23

Speaker 2: It was sort of unveiled at the Giant Screen

00:12:26

Convention in just last fall and it's now getting leases, so we

00:12:32

are anticipating it's being opened in two big theatres in

00:12:36

Canada and then with these Science Centre movies.

00:12:39

What I like about them is that they actually unroll over a very

00:12:44

long period of time.

00:12:45

They don't all come out at once all over the world in all the

00:12:49

same theatres, so it would be some five years or so they would

00:12:53

be unfolding.

00:12:54

We got Michelle Yeoh to narrate , which was a real coup, just

00:12:58

before she got her Oscar.

00:12:59

So we had some good luck there.

00:13:02

Speaker 1: Good luck and exceptional talent To set the

00:13:05

scene for your recent book Skies of Thunder.

00:13:07

You begin by explaining the geographical place names of the

00:13:11

era, which was 1940 through 1945 .

00:13:13

Myanmar is Burma, yangon is Rangoon and Thailand is Siam.

00:13:19

In the second chapter you describe the intricacies and

00:13:22

dangers of constructing the Burma Road.

00:13:25

Can you expand on the urgency and the importance of building

00:13:29

this road?

00:13:30

Speaker 2: The Burma Road is one of those great names.

00:13:34

That is possibly the only part of the story that I had heard of

00:13:39

before actually doing the research and writing the book.

00:13:42

But if you had asked me what it really was, I don't think I

00:13:46

could have told you.

00:13:47

The Burma Road was begun, despite its name, in China.

00:13:52

It was a Chinese nationalist initiative undertaken by Chiang

00:13:57

Kai-shek and begun in 1934 following the defeat of his most

00:14:04

dangerous foe, if you will, the communist.

00:14:07

Chiang Kai-shek had many foe, but the group that he rightly

00:14:13

feared the most in terms of being a direct threat to his

00:14:18

personal power, were the communists, and he had had an

00:14:21

important victory in the south of China, which had forced Mao

00:14:26

and his followers out on their epic 6-mile trek to the

00:14:30

north and will go directly to my capital, which at that point

00:14:48

his new capital was Chongqing, in Sichuan province, on the

00:14:50

Yangtze River.

00:14:51

So work was begun on the road from the adjacent province,

00:14:56

yunnan province, the most southwesterly province in China,

00:15:00

towards to the eastward, to Chongqing, his capital, and that

00:15:05

was done fairly straightforwardly.

00:15:07

Then he began on the second leg , which only advanced about 100

00:15:13

miles, and this was westward, towards Burma, and in fact it's

00:15:18

the westward part, it's the part from Kunming which eventually

00:15:22

did lead to Burma.

00:15:24

That became the classic Burma Road, a route of about 700 miles

00:15:29

or so when all the quirks and turns of the terrain were taken

00:15:34

into account.

00:15:35

But the road languished after this initial start and then,

00:15:41

with new urgency, was begun again in 1937 as the Japanese

00:15:46

threat, which Japanese had been in Manchuria since 1931.

00:15:52

But now there was renewed Japanese activity and one by one

00:15:56

the coasts of China's great long coastline were being.

00:16:00

The ports along the way were being captured and held, and

00:16:04

China began to see that it could in fact be blockaded.

00:16:08

So this vast country, but with a shoreline that's tied up,

00:16:13

didn't leave very many routes of access from the outside world,

00:16:17

and the other routes one coming in from the north, from what

00:16:22

would have been the outlying part of the Soviet Union, was

00:16:25

essentially impractical, beings very, very long and very, very

00:16:29

difficult.

00:16:29

So now the Burma Road, a route into Burma, becomes a kind of

00:16:36

point of not just internal military strategy but really a

00:16:43

kind of route of survival.

00:16:44

And so this becomes a vast enterprise where all along this

00:16:51

route from Kunming and Yunnan province, which was considered

00:16:55

within China to be a very undeveloped backwater province,

00:17:00

with many peoples along the way, who were not Chinese speaking,

00:17:05

were not even ethnically Chinese , and one of the fascinations to

00:17:10

me of learning about this was just to discover how many

00:17:13

different peoples lived along this route as recently as the

00:17:18

late 1930s, when the road is being built.

00:17:27

Late 1930s, when the road is being built, and so it was built

00:17:30

by civilians.

00:17:31

They had some professional engineering oversight, but the

00:17:32

actual manual labor and it was manual, with very few tools was

00:17:36

built by the peasantry Chinese, all the people who'd really not

00:17:41

been conscripted, so children, women, old men, many of them in

00:17:47

undernourished because of the terrible poverty in China, and

00:17:51

particularly that province at the time.

00:17:53

And so it's this extraordinary spectacle of hundreds and

00:17:58

thousands of these civilians being, you know, dutifully

00:18:01

walking out to their levee points where they had been told

00:18:05

you know you need to be at this place on this time and you're

00:18:08

going to be responsible for building this amount of road.

00:18:10

And then they build it.

00:18:12

And the terrain encompasses some of the great river gorges

00:18:17

on Earth, the Salween and Mekong River, for example, these

00:18:21

extraordinary mountains, jungles , forests, and it's a kind of

00:18:27

surreal conjuring.

00:18:30

There's a very good account of it, given by the managing

00:18:33

director, who gives the sort of eyewitness as it unfolds and you

00:18:38

have men hanging from thread-like, not even

00:18:43

scaffolding, just ropes off cliff faces.

00:18:45

They had no dynamite, so they used firecrackers.

00:18:49

Speaker 1: That part of the story fascinated me At every

00:18:52

roadblock, so to speak.

00:18:53

Their ability to devise plans to continue is extraordinary.

00:18:58

Speaker 2: It's this continual improvisation faced with rock

00:19:02

cliff faces.

00:19:03

And how do you make a road?

00:19:07

They're trying to sort of gouge along the side of the cliff and

00:19:10

so they have to create this kind of literal inroad to wind

00:19:16

around the cliff face, and all they have are chisels and hand

00:19:21

tools.

00:19:21

So thousands of they figure out that firecrackers have enough

00:19:26

little gunpowder to make little pitiful explosions that help in

00:19:33

the loosening of this rock.

00:19:35

And so these thousands of squibs are placed, you know, one

00:19:39

by one, into the rock face and lit, and then there's a little

00:19:42

bit of tumbling and then they hammer that out, but all the

00:19:46

time, you know, great peril of their own lives, sort of

00:19:48

dangling on these makeshift lines.

00:19:51

Then they come to the great rivers.

00:19:54

How do you get a bridge across a river?

00:19:56

Well, the first thing you do is you have men strip down, tie

00:20:01

cables around their waist and swim a mile across the raging

00:20:05

river and when they drown, then the next wave comes up and you

00:20:09

just keep coming until somebody makes it across and then they

00:20:13

pull that string and the cable attached to it and you have the

00:20:17

first sort of beginning of a structure across across the

00:20:22

river.

00:20:23

One of the more horrifying things that happened is, as the

00:20:27

road began to be completed, these vast hand-chiseled stone

00:20:33

rollers, weighing you know sometimes many tons, were then

00:20:38

hauled over the broken pebbles and gravels to kind of beat it

00:20:43

all down.

00:20:44

But these were also, if you will, new technologies and there

00:20:49

are counts of people, particularly children, just not

00:20:52

understanding that when you come on a downslope, these behemoth

00:20:58

rollers are going to take on a life of their own.

00:21:00

And there are these horrifying stories of people, particularly

00:21:04

the children, running gleefully ahead of these rollers, like it

00:21:08

was a game, just get crushed in the past.

00:21:10

I mean just an extraordinary account of this remarkable road

00:21:15

built by people who, as several sources pointed out, had never,

00:21:20

in the course of their own history, ever seen a wheeled

00:21:23

vehicle.

00:21:23

So it's going to be a road for lorries carrying supplies, by

00:21:30

definition, but the people's building it have never seen even

00:21:34

a wagon.

00:21:35

All transportation was done by foot or pack ponies.

00:21:39

Speaker 1: This seems like a perfect place to talk about the

00:21:42

Lolo women and the Pendulum women.

00:21:45

I found your descriptions of these two groups of women both

00:21:49

charming and sad.

00:21:51

Speaker 2: So again, mr Tan, who was the managing director of

00:21:55

this enterprise, wrote a wonderful book, a very small

00:21:58

book which you can find on used bookstore sites like Abecom,

00:22:04

called Building the Burma Road, and he gives a wonderful account

00:22:09

of having to negotiate as they travel, moving towards the Burma

00:22:15

border, westward towards the Burma border, passing through

00:22:19

all of these different peoples, and each one has different

00:22:22

customs and different habits and different taboos and different

00:22:27

preferences, and the Chinese engineers sort of have to

00:22:31

negotiate with them one by one and often accommodate their own

00:22:34

preferences.

00:22:35

So the Lolo people were known as the tiger people, very much

00:22:40

feared by everybody, not just people within China.

00:22:45

But when the Americans move in with their air mission, there's

00:22:48

actually a story of some downed airmen being kidnapped by them,

00:22:53

which is a whole kind of other side story.

00:22:56

But they had a very fierce reputation.

00:22:58

But nonetheless, the Lolo women appear and their costume is

00:23:02

this kind of gleaming white tunic, which becomes important

00:23:06

because their strong preference is to work in the dark and they

00:23:11

liked this because it meant they could care for their families

00:23:14

during the day.

00:23:15

Their children have accompanied them and then they can work at

00:23:18

night.

00:23:18

And so the director describes seeing the women you know by

00:23:23

their gleaming clothes in the moonlight, working at night

00:23:28

where all the men were afraid of working at night because this

00:23:32

is when the predators, uh, tigers, so forth, come out.

00:23:35

But, as uh the managing director says, you know, the

00:23:39

lolo women were said to be dead shots with the bow and arrow.

00:23:42

So I always loved that kind of sort of glimpse into these.

00:23:47

You know, women who were so motherly that they wished to

00:23:51

care for their children but would go out at night, you know,

00:23:54

prepared, as it were, to do battle.

00:23:57

But the pendulum women were the Shan women.

00:24:02

Even further west, as you move into Shan country, which is

00:24:06

straddles China, and now into Burma, the country and people

00:24:12

were known as by all travelers as being exceptionally beautiful

00:24:15

and the country had a sort of wonderful climate and a lot grew

00:24:21

there very easily and there was a kind of more indolent way of

00:24:27

life.

00:24:29

And it was also, it has to be said, a place with fierce

00:24:32

malaria.

00:24:33

But when it came to trying to negotiate with the Shan women,

00:24:38

who were, of all the peoples along the way, the least

00:24:42

conditioned to this kind of hard labor, but they knew their

00:24:46

rights, as it will, as few will, and they knew their preferences

00:24:50

and their strong preference was that they wished to carry the

00:24:54

rock debris in baskets balanced picturesquely on one shoulder, I

00:25:00

think, like if we've seen illustrations of ancient Greeks

00:25:04

with amphora carried on their shoulder, sort of very graceful

00:25:06

for a, you know, carried on their shoulder, sort of very

00:25:08

graceful whereas the more practical way and conventional

00:25:18

way to haul off rocks was by balancing a pole across your

00:25:19

shoulder with baskets balanced at each end.

00:25:21

But they remonstrated with the director and they said if we do

00:25:24

that, we can't sway when we walk and we're known as the pendulum

00:25:28

people.

00:25:29

Uh, we must sway when we walk and we're known as the pendulum

00:25:30

people.

00:25:30

We must sway when we walk.

00:25:32

Speaker 1: And so the exasperated managing director,

00:25:34

you know, acquiesced to their demand and the shunned women

00:25:38

carried their baskets gracefully on their shoulders, and this

00:25:42

speaks of the diversity of the people who worked on the road

00:25:46

and, as you said earlier, the poverty in which they lived.

00:25:49

Speaker 2: They were living in poverty and they were levied.

00:25:51

I mean, it has to say that this was a came down as a mandate

00:25:56

from the national government.

00:25:58

You know that they had to comply.

00:26:00

Speaker 1: Yeah, they didn't have much of a choice.

00:26:02

Now you've written about the dangers the workers faced severe

00:26:06

weather, mud, treacherous heights, mosquitoes, other

00:26:10

disease-spreading insects and, of course, predators like tigers

00:26:14

.

00:26:14

Now, apart from Mr Tan's book, how difficult was it to find

00:26:18

primary source information for your research?

00:26:22

Speaker 2: On this particular aspect of the larger story.

00:26:26

This was one of the least difficult parts.

00:26:28

The Burma Road attracted a great deal of international

00:26:32

attention at the time.

00:26:33

It was a huge, vast human enterprise.

00:26:37

It was a moving story, it was a lifeline being boiled by

00:26:42

China's own people in the most kind of heart-rending and

00:26:46

hardscrabble way with their bare hands.

00:26:48

And so there was both a kind of sentimental interest in this

00:26:54

story as well as a more focused interest, which is how well is

00:26:59

this going to work?

00:27:00

Is this, you know, wars looming ahead?

00:27:03

These kinds of supply lines are going to be of interest.

00:27:07

And so there was a great deal of , I'd say, more academic study

00:27:11

from the British side, which looked at things like tariffs

00:27:17

and cargo numbers and the statistics and how much was

00:27:20

actually getting through.

00:27:22

And from the American side there was perhaps more sentiment

00:27:26

.

00:27:26

For example, national Geographic magazine sent a team

00:27:31

to ride the Burma Road and in fact they were never able to

00:27:35

finish it because they got caught by the monsoon.

00:27:38

And therein lay the most cautionary part of this, which

00:27:42

is that how effective really was the Burma Road as opposed to a

00:27:47

grand symbolic gesture?

00:27:48

But anyway, the long and the short is that, from various

00:27:53

points of view.

00:27:54

With few travelers who even rode the road, intrepid people

00:27:58

who went in early, it was possible to get a lot of detail

00:28:03

into that particular part of the story.

00:28:05

Speaker 1: And when did the research become more difficult

00:28:08

In?

00:28:09

Speaker 2: terms of moving chronologically through the

00:28:11

story.

00:28:11

The Burma Road was one of the first parts I really dug into,

00:28:16

and so that material seemed to come very readily.

00:28:19

The rest of the book, I'd say that there was both too much

00:28:24

information from some quarters and not enough information from

00:28:29

others, which I suppose is the way that all big research

00:28:32

projects goes.

00:28:33

But, for example, the uh us air force archives have a plethora

00:28:41

of, I mean thousand, tens of hundreds of thousands of pages

00:28:46

of material, all of which was digitized and sent to me during

00:28:50

the pandemic and this gives the kind of raw logistical data of

00:28:56

the campaigns and of the building this air route and so

00:29:01

forth.

00:29:01

Then there were lots of memoirs privately published recently,

00:29:07

privately published by sons and daughters of participants who'd

00:29:12

found their dad's diary and realized that they could, you

00:29:15

know, wanted to get it out.

00:29:16

There were lots of memoirs from particularly British who'd

00:29:22

lived in Burma or in Northeast India during the time.

00:29:27

I love books that are out of print, so it was fun to just

00:29:31

track them down.

00:29:32

In fact there's a wonderful source you have in Australia

00:29:35

called Asia House, which specializes, as its name sounds,

00:29:40

in obscure books relating to Asia, and I found a number of

00:29:45

wonderful fights there.

00:29:47

But I'd say the part that most frustrated me was, as the story

00:29:53

progresses, there is a big role paid by the Chinese.

00:29:59

Really, peasants who've been recruited is too kind a word who

00:30:03

have been yanked into service to serve in the army that's

00:30:09

eventually going to American-led army, that's eventually going

00:30:12

to go into North Burma, and the experience of these people is

00:30:18

largely told through the eyes of the optimistic eyes and

00:30:23

language of the American trainers, and it was very tough

00:30:27

to find any kind of voice from those people as to how they

00:30:33

actually viewed the experience.

00:30:34

So that was a big, to me, dark hole that I was never able to

00:30:40

fully penetrate.

00:30:41

Speaker 1: And that segues beautifully into my next

00:30:43

question.

00:30:44

On page 106, you write about the inadequacies of navigational

00:30:49

aids on the planes being used to fly over the hump.

00:30:52

Can you explain where the name the hump derived and the terrain

00:30:57

that made this area extremely dangerous to navigate?

00:31:00

But before you do, there's something I wanted to talk about

00:31:03

at the beginning of the book.

00:31:04

In the prelude, which to me had the book reading almost like a

00:31:09

thriller, Prelude, which to me had the book reading almost like

00:31:13

a thriller you give excerpts from pieces written by pilots

00:31:15

talking about their experiences flying over the hump and they

00:31:19

are remarkable and it makes narrative nonfiction wonderful

00:31:23

to read, exciting to read.

00:31:27

Speaker 2: There are a number of factors that made this

00:31:29

terrifying, and that's perhaps unusual is how layered the

00:31:34

difficulties were.

00:31:35

So the hump specifically refers to this is the air supply of

00:31:42

China from India, largely run by the US Air Forces, although

00:31:48

there are other participants.

00:31:50

There's a commercial American-Chinese commercial

00:31:54

operation that did a valiant service called the Chinese

00:31:58

National Aviation Corporation, and there were some RAF and

00:32:03

Australian pilots also, by the way who participate in it.

00:32:06

But largely this is an American operation and they start from

00:32:11

northeast India in the province of Assam and fly to the nearest

00:32:18

point in China, which is, or the nearest feasible point in China

00:32:22

, which is Kunming, the capital of Yunnan province, which is the

00:32:26

province closest to Burma.

00:32:28

So in the middle of this there is Japanese-occupied Burma and

00:32:33

in the middle of this is the Japanese.

00:32:35

Not just Japanese-occupied Burma, but one of the great,

00:32:39

vast jungle areas of the world.

00:32:41

The hump refers to a ridge along this route that specifically

00:32:48

rises between, if you're coming from the West, from India,

00:32:52

between the Salween and the Mekong River and in the Hengduan

00:32:58

Mountain, larger Hengduan Mountain range.

00:33:01

But that very narrow ridge came to stand, was named the hump,

00:33:07

just with kind of airman slang, and was named the hump just with

00:33:11

kind of airman slang.

00:33:12

We're flying the hump, we're flying the rock pile was another

00:33:14

phrase that they would give, but it also came to stand for

00:33:17

the entire route.

00:33:18

So flying the hump essentially meant the whole route.

00:33:21

What made this so difficult?

00:33:24

It's hard to even know quite where to start, but let's start

00:33:28

just with the route.

00:33:29

The route, if flown absolutely correctly, never really had to

00:33:37

surmount anything higher than about 15 feet.

00:33:41

There was a way point along route, lycian Mountain, which

00:33:46

rose to about 18 feet, which one flew.

00:33:49

It was a landmark to sort of turn the corner to the southeast

00:33:52

, but that was about the height that the aircraft alone had to

00:33:58

accommodate.

00:33:58

However, on a clear day, visibly on all sides of this

00:34:03

route, well within a hundred miles, were mountain peaks of

00:34:07

the Himalayas which rose vastly higher.

00:34:11

So the first thing that was imperative was that this route

00:34:15

had to be stuck to pretty closely.

00:34:17

If you deviated you would be in great danger.

00:34:21

The first challenge was that the maps and charts themselves

00:34:25

available when this operation began, which was in 1942, were

00:34:29

very, very faulty, and there were errors in every direction.

00:34:33

Sometimes mountains ranges were listed higher than they

00:34:36

actually were, sometimes they were lower, and so that in

00:34:39

itself was very, very destabilizing.

00:34:41

The second point is that there were initially, particularly

00:34:47

when it began, no navigational aids en route whatsoever.

00:34:53

So you had a compass and a heading and a kind of airspeed

00:34:58

indicator, but there were no air traffic control.

00:35:03

There was initially just one beacon that was put in I think

00:35:06

it was January of 1943, which was just a kind of allowing you

00:35:11

to have a landmark as you headed over the Burma jungle, but very

00:35:17

much pilots were flying essentially like ships sailing

00:35:22

by dead reckoning.

00:35:23

Later on, in the course of the, as this was sort of developed

00:35:27

out, there were radio stations, but these were mostly at the

00:35:31

destination.

00:35:32

They weren't along the route, because along the route was

00:35:36

Japanese occupied Burma.

00:35:38

So you would get some aid as you came in, maybe within 200

00:35:43

miles if you had perfect conditions, more likely within

00:35:48

25 miles if conditions were less than perfect as you came in

00:35:52

towards your destination.

00:35:54

But in the midst of all of this was the what was arguably the

00:35:58

worst aviation weather system in the world, and this was a

00:36:05

diabolical convergence of both very moist low systems coming

00:36:12

from the Bay of Bengal on the west and the South China Sea on

00:36:18

the east, then combining with these very diabolical dry, cold

00:36:23

winds that come rushing down from Tibet and from Siberia, and

00:36:28

the convergent meant this kind of chronic maelstrom of

00:36:33

turbulent weather, in addition to which you have the mountains,

00:36:38

and mountains, as any pilot would tell you, can cause what's

00:36:43

called mountain wave effects, which is when high winds slam

00:36:47

against the mountainside and then create a kind of wind shear

00:36:50

that can even today, you know, one has to be very wary of, can

00:36:55

flip planes, invert planes, aircraft.

00:36:58

So you had these weather conditions, on top of which you

00:37:03

had a monsoon kind of climate, so there were these periods of

00:37:07

just intensely solid rainfall, and on top of all of that, the

00:37:14

thing airmen perhaps feared most of all was ice, and the ice

00:37:19

conditions were extreme.

00:37:21

They not just encountered a long route, but at vertically,

00:37:28

so from 9 feet all the way up to 26 feet.

00:37:33

Which brings us to the final factor, which is the

00:37:37

capabilities of the aircraft.

00:37:38

At that time these were not aircraft like today where we can

00:37:43

fly from, you know, sydney to Cairn at 26, 28, 30 feet,

00:37:50

40, 42 if you're flying other routes.

00:37:54

These had a kind of cruising ceiling of about 20 feet,

00:38:00

and some of the later aircraft could go up comfortably to 26,

00:38:05

28 when empty.

00:38:07

But you start to put all of that together 28 000 when empty.

00:38:11

But you start to put all of that together and imagine being

00:38:14

a pilot who takes off and expects to fly, solid

00:38:22

instruments all the way, with very few navigational aids, with

00:38:23

winds that press him off course , navigating by dead reckoning

00:38:26

or the seat of his pants and knowing that any margin of error

00:38:31

means that he may be landing on a mountain peak, somewhere that

00:38:34

he can't see.

00:38:35

Speaker 1: It must have been terrifying.

00:38:37

Speaker 2: Yeah.

00:38:38

Speaker 1: And I enjoyed the pilot's backstories that you put

00:38:41

into the book.

00:38:41

Did you happen to read Robert T Booty's book Food Bomber Pilot?

00:38:46

Speaker 2: Yes, that's actually one of my, I'd say, most

00:38:49

valuable sources.

00:38:51

Bob Booty was a pilot who came over to India, initially to be a

00:38:57

fighter pilot and through he had fallen in love and become

00:39:04

engaged with a nurse on the long sea voyage over and once he was

00:39:10

sort of established in his barracks, his very makeshift

00:39:18

basher barracks in India, he decided he would just fly on

00:39:23

over to visit her.

00:39:24

And I have to say I think fighter pilots tend to be, I

00:39:29

think it's necessary that they're cockier than other

00:39:32

pilots.

00:39:33

I'm proud to say my partner was a former Navy pilot who flew in

00:39:39

Vietnam, and I think he would acquiesce to that actually.

00:39:43

But anyway, bob Booty felt that he had clearance to go over and

00:39:49

see his fiancee and it turned out that the authorities saw it

00:39:53

very differently and so he was charged with going AWOL and as a

00:39:57

result of which, when the dust settled, he had been demoted

00:40:02

from being a fighter pilot to an air transport command pilot.

00:40:05

Now, this is of interest for many reasons.

00:40:09

One then Bob Booty's wonderful diary starts tracking the story

00:40:15

I'm tracking, which is of course air supply and the hump and so

00:40:20

forth, but it's very, very indicative in what low esteem

00:40:26

the air transport command pilots were held, because to be

00:40:31

demoted to one of them is a very eloquent way of saying you've

00:40:36

been put down with the people we regard as the lowest of the low

00:40:40

, and so I think one of the things that was very

00:40:44

demoralizing from the outset was that, you know, the fighter

00:40:48

pilots were top of the totem pole, if you will, and then

00:40:51

below them are the bombers, and then below them maybe the

00:40:55

evacuation planes, but at the very, very bottom are just cargo

00:40:59

pilots who are truck drivers in the view of the kind of

00:41:03

established hierarchy.

00:41:04

And indeed the acronym of the Air Transport Command, atc, was

00:41:11

cynically used by people outside the services, saying it meant

00:41:15

allergic to combat.

00:41:16

So they were sort of looked down upon as being non-combat

00:41:22

pilots, and yet here they were flying this inherently very,

00:41:25

very dangerous mission, very, very dangerous mission.

00:41:33

So Budi is a wonderful voice in that you see him having to

00:41:35

adapt to this task for which he's not trained.

00:41:36

He was obviously a very skilled pilot and survives the war,

00:41:41

although has an accident really not of his making at the very

00:41:45

end that takes him out of service.

00:41:47

But it does underscore another point, which is that the pilots

00:41:53

who were funneled into the Air Transport Command were the least

00:41:57

trained.

00:41:57

The most trained pilots are going on what are recognized as

00:42:02

the big, important missions in Europe, in North Africa, as

00:42:06

fighters and bombers.

00:42:08

There are stories.

00:42:09

I actually interviewed one pilot, a lass who's passed on

00:42:13

since I spoke to him, but he described arriving and being

00:42:19

told to collect with a friend, a C-46, which was the new, bigger

00:42:25

cargo plane that had just come into the theater, and had a lot

00:42:29

of problems with it, by the way.

00:42:30

And they arrived.

00:42:32

They had known it was a c46 and they arrived to find it and

00:42:36

they had never seen one before, they had never been instructed

00:42:39

in one before, and he said we literally had to figure out how

00:42:42

to open the door.

00:42:43

And then they got in and read the manual as they taxied sort

00:42:48

of desolatory back and forth and then he flew it first to

00:42:52

Calcutta where, just because it was a new plane and it had to go

00:42:55

there and that was the protocol , and then took it over the hump

00:42:59

.

00:42:59

But there are stories of pilots arriving with 25 hours of

00:43:03

instrument training, which wouldn't get you a pilot's

00:43:08

license I don't think today and yet they were then thrown into

00:43:12

these severe conditions.

00:43:14

So I think the level of fear was not just because the

00:43:18

situation was inherently difficult, but because, as one

00:43:34

executive said, look, the kids are flying over their head, was

00:43:35

how he put it.

00:43:36

And so the protocol was the more seasoned pilots would fly

00:43:38

and the junior just arrived pilot would sit as co-pilot in

00:43:39

the right seat a certain number of hours, but that was their

00:43:44

training and sadly, many of them didn't make it home.

00:43:47

Speaker 1: In your book you quoted something like 600 planes

00:43:51

are littered across this flight path.

00:43:53

That is an extraordinary amount of planes.

00:43:57

Speaker 2: The way I came on this story was I was on

00:44:00

assignment for National Geographic magazine on a story

00:44:04

about tigers, and I was in the north of what's today Myanmar,

00:44:10

in this amazing place called the Hukong Valley, which is today

00:44:16

holds the world's largest tiger reserve and is a spectacular

00:44:22

wild jungled area, but was in fact that area over which the

00:44:29

pilots were flying?

00:44:31

And very few people go into this area today, really only

00:44:35

wildlife officers or poachers.

00:44:37

And so I was talking to the wildlife team about their

00:44:41

stories and so on, and there were some Naga villages

00:44:48

scattered throughout this and they had these very strange

00:44:50

metal fences around their vegetable plots, and when I

00:44:52

commented on them, the wildlife officers said, oh, they cut

00:44:55

those from the fuselages of the cargo planes in the jungle.

00:44:59

And that was how I learned of the story.

00:45:01

And they one of the officers said that he'd been on a patrol

00:45:05

some years before and come on a downed aircraft, he and his team

00:45:09

, which had the skeleton of the pilot still strapped into the

00:45:13

left seat, and I couldn't believe this that cargo planes

00:45:19

just would vanish, be buried in the jungle still.

00:45:22

And then, when I came back to the States, I looked into it and

00:45:26

I was told that the estimate is about 600 are still

00:45:30

undiscovered and that I would say, and I think most people

00:45:34

would say, is a very conservative figure.

00:45:37

The record keeping was very spotty, particularly during the

00:45:41

first year or so of this operation, and other records

00:45:46

speculate that there are as many as you know, more like 1.

00:45:50

But we'll never know that they just people, the planes either.

00:45:55

Sometimes they were found after a crash, because you would see

00:45:59

an explosion and smoke and a pilot flying over could spot it,

00:46:03

but often they just vanished just into silence.

00:46:07

And this is something one of the pilots wrote about in his

00:46:10

memoir.

00:46:10

He said you know, we'd all wait and wait for this plane we knew

00:46:14

was meant to come in and we'd hope it had been diverted to

00:46:17

another airfield.

00:46:18

We'd hoped it might have stayed overnight somewhere, but then

00:46:22

it never appeared.

00:46:23

Never appeared, just silence.

00:46:25

So that was the fate of some aircraft and another others.

00:46:30

Were the crews bailed out?

00:46:32

If they got lost, if they had engine trouble, if they would

00:46:36

run out of fuel because they were lost, they would parachute

00:46:40

out and the aircraft, you know, would drift on to crash

00:46:43

somewhere.

00:46:44

Speaker 1: Maybe found, maybe not found and if we just think

00:46:47

about that figure for a moment, 600 to 1200 planes, that's a lot

00:46:52

of money the US had invested in this region of the war.

00:46:56

And that kind of leads me to this question, because I'm

00:46:59

interested in your thoughts on how did British colonialism

00:47:04

affect what the Americans were wanting to do in this

00:47:07

geographical area of World War II, and how did Churchill and

00:47:11

Roosevelt differ and thought similarly about China at this

00:47:16

time?

00:47:17

Speaker 2: I would flip it around, I would say the driving

00:47:19

dynamic of this hump operation was what the British regarded as

00:47:25

an American obsession with China, and it could not be

00:47:30

shaken.

00:47:30

It was very unclear quite what the objectives of this great

00:47:37

heroic airlift was.

00:47:39

So at the very beginning, from correspondence that came back

00:47:45

from advisors, american advisors , who were sent over to sort of

00:47:49

examine the situation of China, as you know Japanese have the

00:47:54

war has already begun, if you will, in China, earlier than it

00:47:57

will, if one considers the Japanese invasion of China to be

00:48:02

, you know, part of the larger war as it eventually becomes.

00:48:07

So American advisors were going over and they come back with

00:48:12

actually brutal assessments of Chiang Kai-shek, both as a

00:48:16

person, as a leader and as capabilities.

00:48:19

But they believe that having the japanese continue to occupy

00:48:26

china is good for the wider war effort because it will tie down

00:48:32

those forces as in in a kind of occupying situation which could

00:48:37

otherwise be unleashed to cause harm, particularly as the

00:48:41

pacific war, you know, looms into focus.

00:48:44

So the first kind of objective is that this will keep China

00:48:51

from collapsing, and by collapsing essentially they mean

00:48:55

selling out to the Japanese.

00:48:57

At the same time, every advisor from every nation understood

00:49:04

clearly that Chiang Kai-shek would never sell out or fall to

00:49:08

the Japanese, that his own grasp of power, his own thirst for

00:49:15

power was so strong he would never put himself in that

00:49:17

position and also his hatred of the enemy was very real.

00:49:21

So this collapse that's always threatened and which Chiang

00:49:26

Kai-shek threatens the allies with too, that if he doesn't get

00:49:29

this loan, if he doesn't get this a billion dollars worth of

00:49:33

gold one of his demands is, if he doesn't get 10 tons a

00:49:37

month over the hump in supplies, china could collapse, her

00:49:41

morale would collapse, and it's always a threat that he

00:49:44

continually wields.

00:49:45

But it's unclear really what that would have entailed.

00:49:49

And certainly a lot of the airmen actually who had come to

00:49:55

know China said, you know well, even if they did, there were so

00:50:00

many other warlords, there were so many factions, there were

00:50:04

also the communists that it was never as if the Japanese could

00:50:07

have just, you know, bailed out and got somewhere else.

00:50:10

They were going to have to be in it one way or the other.

00:50:13

So the first sort of sketched objective is that this holds

00:50:19

down the Japanese in the war.

00:50:21

But the second objective, which is stated with much more

00:50:24

clarity by the Americans, and by Roosevelt in particular is that

00:50:29

the end of war objective is that China will be this great

00:50:35

democratic ally and particularly close to the United States,

00:50:41

that the United States having shown all this goodwill and

00:50:47

fought as an ally, as, if you will, with Chiang Kai-shek, that

00:50:51

the inevitable result afterwards would be these four

00:50:55

powers Britain, the United States, soviet Union and China

00:50:59

but that China would be very firmly attached and beholden to

00:51:04

American leadership and, in other words, a very close and I

00:51:08

would almost want to say cynically manipulated ally.

00:51:11

That was the view, and Roosevelt prided himself on his

00:51:16

knowledge of China.

00:51:17

His maternal grandfather had made a fortune in tea and opium

00:51:25

in China and he liked to refer to this and he would tell people

00:51:29

you know, I have 100 years of history of China myself and my

00:51:32

family, so there was a kind of sense that he knew what he was

00:51:37

doing and genuinely looked forward to this kind of great

00:51:42

new balance of power which, amongst other things, would

00:51:46

diminish the European and specifically British power in

00:51:50

the East and would increase American power in the East by

00:51:54

being so closely allied to China .

00:51:56

So a lot of geopolitical maneuvering and objectives here,

00:52:00

and so out of this comes all of these campaigns, the Hump

00:52:07

campaign, the land campaign through Burma, and the British

00:52:11

had an entirely different view of the value of China.

00:52:14

They did not believe in Chiang Kai-shek, they did not believe

00:52:18

in the fighting power of the Chinese troops and army, which

00:52:23

they knew to be starved of both food and supplies and leadership

00:52:28

often, and they did not believe in this vision of the post-war

00:52:34

kind of reality.

00:52:35

And indeed there's some memos that are written by sort of

00:52:40

British-Chinese experts that said look, there's nothing we

00:52:43

can do.

00:52:44

There's going to be a civil war and it's quite possible that

00:52:48

the communists, who have, you know, this number of force

00:52:52

behind them and better policies and so on, are going to win and

00:52:55

there's nothing we can do about it.

00:53:01

The British well, what can you do?

00:53:06

Based on very deep analysis and the American optimist we can't

00:53:12

do nothing, you know.

00:53:14

Of course we must try, of course we can make it work, and

00:53:18

bold big ventures are done by that latter view.

00:53:21

You know, building the hump, airline, I guess, sending people

00:53:29

to the moon, you know all of these impossible things.

00:53:31

So one can admire that can-do, must-do kind of spirit that I

00:53:32

think is very American and very entrepreneurial American.

00:53:36

But sometimes reality thwarts that best optimism, as it

00:53:43

clearly did in this case.

00:53:46

It's safe to say that the British and Americans, who were

00:53:51

allies, were also deeply suspicious of each other's

00:53:54

motives, particularly in this particular theater China, burma,

00:53:59

india the Americans were intent on fighting a land war, and the

00:54:04

reluctance of the British to be dragged into a land war in

00:54:07

Burma made the American think that the British wanted the

00:54:11

Americans to fight their war, whereas in fact I think

00:54:15

Churchill would have been happy to have had no Burma campaign

00:54:19

and to have said simply look, the Japanese are in there, we

00:54:23

cut off their supply lines, they're going to starve and have

00:54:26

to retreat or just die in the jungle outposts.

00:54:31

If we blockade Rangoon, for example, on the one hand, and

00:54:35

we're on the other side in Siam, we can hold them down.

00:54:40

So it's a fascinating conflicted sort of situation

00:54:47

amongst these close allies in what is already an entirely

00:54:51

chaotic and very difficult theater.

00:54:53

But it's safe to say that I think the one thing Churchill

00:54:58

and Roosevelt did agree on was ultimately on the value of one

00:55:06

the air supply and two air bases being built in China for a

00:55:13

projective offensive.

00:55:14

That, by the way, never happened.

00:55:16

Certainly the British voiced support for it, churchill voiced

00:55:20

support for it, but I believe that actually they only voiced

00:55:24

support for it because they thought it would deflect

00:55:26

attention from a land campaign.

00:55:28

I'm not convinced the British actually really supported the

00:55:33

idea of any of these very messy campaigns, whether it was the

00:55:38

air operation in China or the air supply to China.

00:55:42

Speaker 1: I'd love to talk about your research and writing

00:55:45

process.

00:55:46

You mentioned that you began writing this book or researching

00:55:48

this book during the pandemic.

00:55:49

Can mentioned that you began writing this book or researching

00:55:49

this book during the pandemic.

00:55:51

Can you talk a little about this and the amount of time you

00:55:54

spend on research before starting to write?

00:55:58

Speaker 2: Yes, I was very fortunate to have got the

00:56:02

commission ahead of the pandemic , because it's wonderful to have

00:56:06

a big juicy project while people are on lockdown.

00:56:09

And I found that the archives that I needed were very

00:56:15

accessible remotely.

00:56:16

I mentioned in particular the Air Force archives in Alabama,

00:56:22

for example, that were very timely in sending out these

00:56:26

reels and reels of material timely in sending out these

00:56:29

reels and reels of material.

00:56:30

You know, as a freelancer I have the luxury of deciding what

00:56:36

my next, or hoping to decide what my pitching my next project

00:56:37

in any case, and I had done this based on my experience in

00:56:42

the Hukong Valley of coming away with this vision of these

00:56:47

fences cut from the fuselages and so on and very little else.

00:56:53

I knew nothing.

00:56:54

I had had a great aunt who had worked in Burma, as it was still

00:56:58

called for the World Health Organization, and so I love the

00:57:02

name of that country and I had sort of been drawn to the

00:57:05

country and I love traveling in modern Myanmar at that time.

00:57:11

But the things that I thought I knew well, even about the

00:57:14

Pacific War.

00:57:15

I realized how sketchy my knowledge really was, and so

00:57:19

there was a wide amount of reading just to get the context

00:57:23

of the theater, of what was going on, of who was who, of

00:57:27

what the objectives were, before one could even get down into

00:57:30

the details of the hump.

00:57:32

But the only thing I can say is it's some of the most

00:57:36

fascinating reading I've ever done.

00:57:39

It was from memoirs of people growing up on tea estates in

00:57:44

Assam to these extraordinary accounts by the pilots who

00:57:49

survive walkouts, you know, after they bail kind of

00:57:52

extraordinary background of the big powers playing out, both

00:58:12

grappling for the future after the war and hoping to actually

00:58:16

win the war.

00:58:17

It's just amazing stuff.

00:58:19

Speaker 1: Yes, it is Okay.

00:58:21

What are you currently reading?

00:58:23

Speaker 2: Well, one thing I'm doing is mopping up on things

00:58:26

that I never quite read thoroughly.

00:58:29

My favorite is the diaries two-volume published diaries of

00:58:36

General Henry Arnold, known as Hap Arnold, who was the chief of

00:58:41

staff of what was then the US Air Forces.

00:58:45

I love these diaries from the era and of course I read closely

00:58:50

the parts that pertain to my story.

00:58:53

He was building the American Air Force really from the start,

00:58:58

not quite from scratch but almost from scratch, and there

00:59:02

are many theaters of war that he was having to be involved in,

00:59:06

every detail of it, and it's just a very uncomplicated, very

00:59:11

nuts and bolts type of writing, very refreshing, and I'm

00:59:15

enjoying that.

00:59:16

Next, what I'm just starting, is a wonderful book by a scholar

00:59:21

of the Aegean and I guess you'd say the Aegean and Greek Bronze

00:59:26

Age, called Geoffrey Emmanuel, called Black Ships and Sea

00:59:31

Raiders, which is about the well , it sounds very dry but it's

00:59:38

quite interesting the sea peoples and the migrations that

00:59:42

brought down the Bronze Age, and so it very much overlaps with

00:59:47

the Homeric narrative.

00:59:50

So I'm very interested in that.

00:59:51

And finally, there's a writer of fiction I haven't read in a

00:59:56

while, but Henry Williamson, probably best known.

01:00:00

He wrote Tarka, which was a sort of beloved children's book

01:00:05

in England but he had been in the First World War and wrote a

01:00:10

12-volume autobiography that's sort of disguised as fiction and

01:00:16

I'm about halfway through and I had to put it aside for this

01:00:20

book and I'm going to go back to that.

01:00:22

Speaker 1: It sounds like you have your reading cut out for

01:00:25

quite a few months the rest of my life.

01:00:27

I think, reading cutout for quite a few months, the rest of

01:00:29

my life, I think, caroline, you are a vessel of knowledge and,

01:00:34

as the text on the back of the book says, skies of Thunder is a

01:00:43

masterpiece of modern war history, and I'm always

01:00:44

surprised at how many people are interested in planes from World

01:00:46

War II.

01:00:46

Yes, me too, actually.

01:00:46

In planes from World War II.

01:00:47

Yes, me too, actually.

01:00:49

Thank you so much for being a guest on the show, caroline.

01:00:52

It's been a pleasure chatting with you, thank you.

01:00:56

Speaker 2: Well, thank you, and I have to say that, as you know,

01:01:00

my great friend Lynn Cox, who you interviewed earlier, had

01:01:08

told me that this would be the best interview I'd had, so I

01:01:09

just wanted to pass that along also.

01:01:11

Thank you very much.

01:01:12

Speaker 1: Well, I hope you enjoyed this conversation,

01:01:14

because I certainly did.

01:01:16

Yes very much.

01:01:17

Thanks again, caroline.

01:01:19

Thank you Bye-bye.

01:01:20

You've been listening to my conversation with Caroline

01:01:24

Alexander about her new book Skies of Thunder the deadly

01:01:28

World War II mission over the roof of the world.

01:01:31

To find out more about the Bookshop Podcast, go to

01:01:35

thebookshoppodcastcom and make sure to subscribe and leave a

01:01:39

review wherever you listen to the show.

01:01:41

You can also follow me at Mandy Jackson Beverly on X, instagram

01:01:47

and Facebook and on YouTube at the Bookshop Podcast.

01:01:51

If you have a favorite indie bookshop that you'd like to

01:01:54

suggest we have on the podcast, I'd love to hear from you via

01:01:58

the contact form at thebookshoppodcastcom.

01:02:01

The Bookshop Podcast is written and produced by me, mandy

01:02:05

Jackson-Beverly, theme music provided by Brian Beverly,

01:02:09

executive assistant to Mandy Adrian Otterham, and graphic

01:02:13

design by Francis Ferrala.

01:02:14

Thanks for listening and I'll see you next time.